Levelling Up

REGIONAL INEQUALITY in the UK is at epidemic levels.

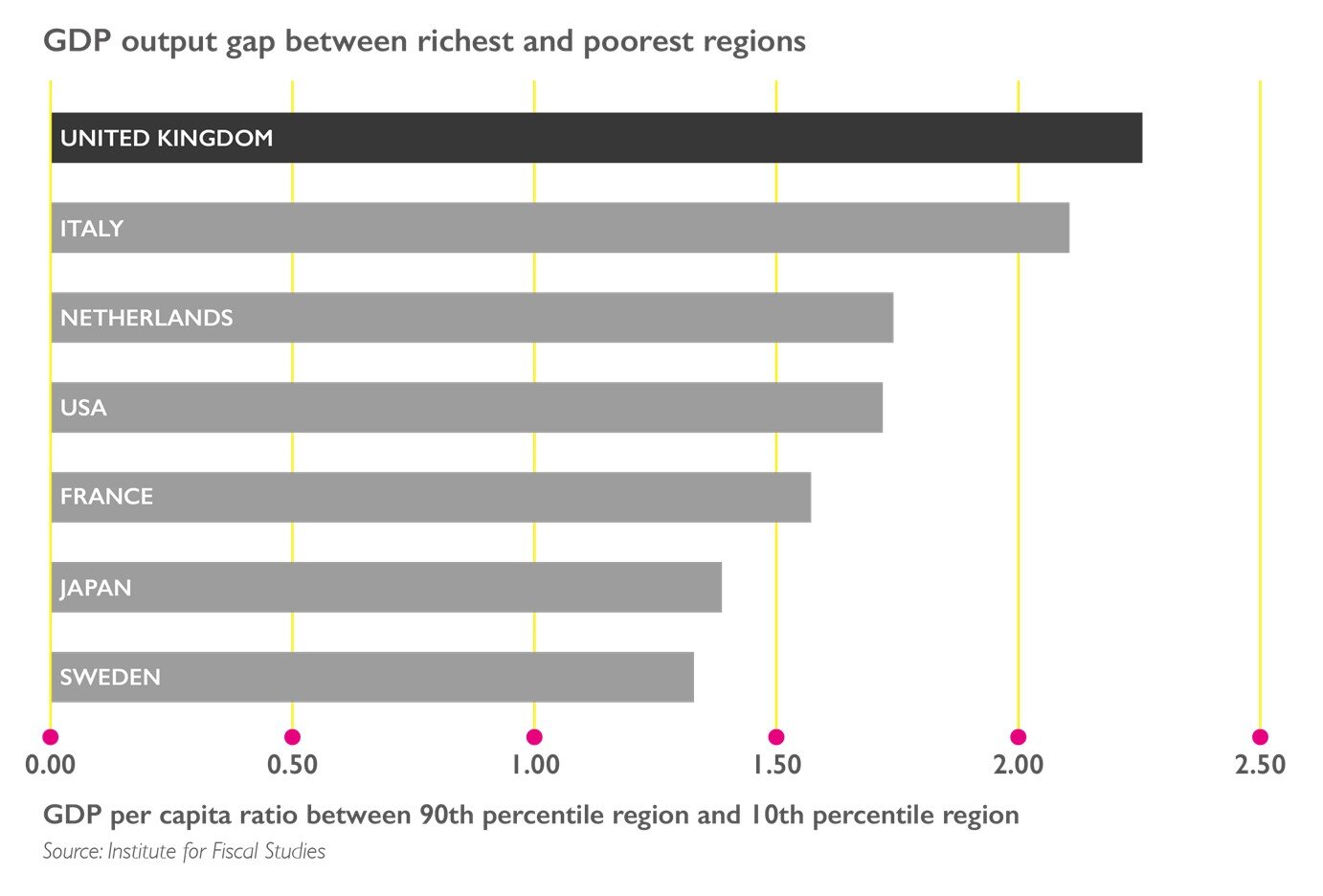

Extensive research makes clear that the UK is one of the most regionally imbalanced countries in the developed world. In 2020 the Economist reported that in the richest parts of the country (Camden and the City of London) GDP per capita is now thirty times larger than in the UK’s poorest areas (Ards and North Down in Northern Ireland).

Regional inequalities are now as wide again as they were in 1900, after disparities in wealth decreased during the twentieth century manufacturing boom.

This is in part because of the investment in transport, education, skills, housing and community infrastructure that act as a self-reinforcing cycle, leading London and the South East to benefit from a virtuous circle. For places that have been left behind, often former industrial regions and isolated rural areas, it is a vicious one, and these opposing trajectories only serve to exacerbate regional disparities.

Source: Institute for Fiscal Studies

Inequality of this kind has serious consequences. There is now a nineteen-year difference in healthy life expectancy between the UK’s most prosperous and deprived regions. A quarter of children living in poverty are concentrated in just 10% of the country’s local authority areas. While household wealth grew by nearly 80% in London between 2006 and 2018, it fell by 12% in the North East and East Midlands over the same period. Students in London are twice as likely to be attending ‘outstanding’ schools, more likely to study STEM subjects and are significantly more likely to go to university than students from more deprived areas in the UK’s northern regions. However, this is not just a problem for those living outside of the UK’s few wealth and productivity centres. As reported in the book The Spirit Level, inequality of this kind reduces key wellbeing indicators for everyone, regardless of social class. More equal societies see better outcomes in education, health, crime, drug use, social mobility and community trust, to name just a few examples, than less equal societies, even for those at the top of the pyramid (relative to analogous individuals in less equal nations).

With the Brexit deal concluded, addressing geographic inequalities by ‘levelling up’ has been pushed to the top of the policy agenda. Boris Johnson made it clear in his very first speech as prime minister, that boosting economic performance outside of London and the South East and reviving the fortunes of the ‘left-behind’ towns and cities of the UK is a major priority for his government. However, this is an ambitious agenda that is unlikely to be achieved with off-the-shelf solutions; even well-designed policies could take years or even decades to have meaningful effects. To alleviate the endemic inequality of the UK, the considered allocation of public funds and the incentives that drive private funds into those regions and industries will be crucial.

Although infrastructure investment is rarely considered to be the frontline of the battle for social equality, people, communities and businesses need infrastructure to thrive. In mitigating regional disparities, both public and private infrastructure investments have a critical role to play, as do the logistics and strategies of the construction industry itself.

Reducing inequality depends on the creation of social infrastructure, which includes affordable housing, the establishment of new roads and railways, the physical extension of services like broadband and wireless coverage and the building of new schools, hospitals and office space, among other examples. Furthermore, there is a well-established correlation between deprivation and poor environmental conditions (such as poor air quality), meaning that our transition towards a greener economy also has social policy consequences. While construction is not typically considered to be a vital cog in the social justice machine, the mechanisms by which new infrastructure is built and financed can actually be the difference between continuing deprivation and meaningful transformation.

Responding to calls from think tanks, such as the Centre for Policy Studies, the release of the National Infrastructure Strategy included the announcement of a new £4 billion Levelling Up Fund for investment in local infrastructure in England (with further monies for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland). This package reflects Whitehall’s acknowledgement that expenditure on physical investment, including certain aspects of vital infrastructure, has been persistently low. Indeed, a Treasury paper states that UK investment as a share of GDP has ranked in the lowest 25 per cent of OECD countries for 48 of the last 55 years, and the lowest 10% for 16 of the last 21 years. The UK’s infrastructure was also ranked 11th in the World Economic Forum’s 2018 Global Competitiveness Report, with the WEF noting that the ‘inadequate supply of infrastructure’ is the second most problematic factor for doing business in the UK.

The publication of the National Infrastructure Strategy and the creation of the new cross-departmental fund signals a transition away from a fragmented funding landscape to a more cohesive and strategic solution. The role of actors in the construction industry, however, should go beyond simply lobbying for more money (and for that money to be dispersed across the nation). Building faster, greener and better in a manner that strengthens the nation as a whole, is a new concept of value and demands adaptation of the industry.

Social impact assessment is expected to become a mainstay of business cases (reinforced by the government’s procurement policy note PPN06/20) and a precursor to securing future funding. The construction industry will need to collaborate to establish a robust and consistent definition of social value, a common language and a framework for evaluation. Putting words into action, we are working through TIES Living Lab with Social Profit Calculator to establish this principles for infrastructure developments, however a broader cross-industry reach is required. Furthermore, with limited access to historical data banks, data collection revealing the social impact of infrastructure, will become increasingly relevant in establishing priorities for areas that have been ‘left behind’.

It is important to note, though, that greater and more geographically diversified investment on infrastructure cannot address the vast regional inequalities of the UK alone. Two other key areas that could transform poor regions include, the devolution of power from London to local authorities and a renewed emphasis on improving educational outcomes. These solutions are intertwined: improving education in disadvantaged areas is an integral component of drawing investment in infrastructure or other sectors in the future. More devolved power will give local authorities the opportunity to support projects that will have the biggest impact on their communities, thus increasing the possibility that new infrastructure ventures will have a tangible positive impact on inequalities.

These dynamics illustrate the complexity of the UK’s regional inequalities. With mutually reinforcing factors of such inequalities, the disparity between regions of the UK has hit its highest level for a century and continues to widen, with severe consequences for those residing in underfunded regions. We believe that the construction sector has a key role to play in tackling this issue, by incorporating social considerations into its practices and building an industry that is safer, more inclusive and sustainable. Through this, we will be able to deliver better social and physical infrastructure that can be a catalyst for real change and a part of regional revitalisation. With inequality in the UK reaching historic levels, it is more important than ever to ask what can be done to alleviate these persistent injustices, and to act upon the responses without delay.

This article is the work of the brilliant Ellie Hopgood. Talented and passionate about realising positive change – please have a look at her own website here: https://endlesslyrestless.com/